In ‘Mission Bengal’, Snigdhendu Bhattacharya traces Hindu nationalism, hurt and anger to 19th-century Bengal.

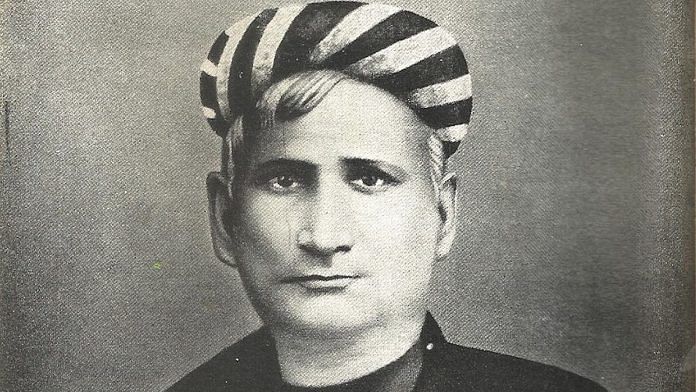

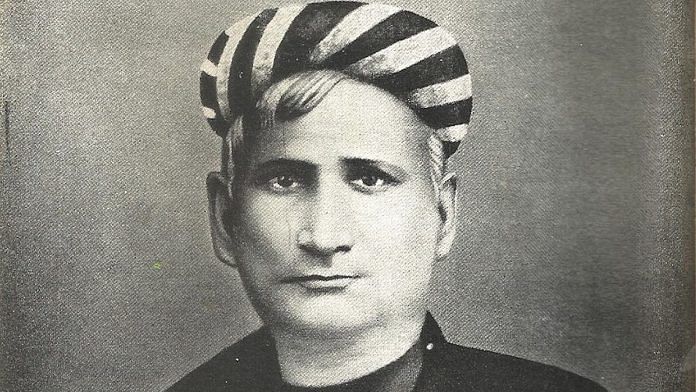

A portrait of Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay | Wikimedia Commons

Nineteenth-century Bengal, the time and theatre of the Indian Renaissance from where many aspects of modern India originated, was also the birthplace of the idea of Hindutva, which the RSS describes as Hindu cultural nationalism. The very word Hindutva, the concept of Bharat Mata and the Bande Mataram slogan were all products of Bengal that spread across the country. The origin of the notion that Hindus are in danger – the principal reason that led to the creation of right-wing Hindutva organizations – can also be traced back to Bengal.

Hindu revivalism emerged in Bengal in the second half of the nineteenth century as a reaction to the influence of Western education and culture on the Hindu society during the first half of that century.

Brahmoism was a monotheistic socio-religious reformist movement born out of the Hindu society’s exposure to Western education. This movement sowed the seeds of the Bengal (or Indian) Renaissance. The movement denounced idolatry, faith in scriptures and avatars, and discrimination based on caste, creed and religion; it questioned superstitions and advocated women’s education. Its journey started with the foundation of the Brahmo Sabha in 1828 by ‘Rajah’ Rammohun Roy, the social, religious and educational reformer often regarded as the ‘father of Indian Renaissance’ and the ‘father of modern India’, and Debendranath Tagore, father of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore.

The visualization and depiction of India as a ‘mother’ started gaining popularity during the late 1860s. The first published reference to the coinage ‘Bharat Mata’ has been traced to a satirical Bengali book, Unabingsho Puran (the nineteenth purana), published in 1866 under the pseudonym of Krishnadwaipayana Vedavyasa. Bhudeb Mukhopadhyay, a scholar and writer, is generally regarded as its anonymous author. He was part of Bengal’s Hindu revivalism. Discussing Mukhopadhyay and his times, linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterjee wrote that the atmosphere in the colleges and high schools during 1840–1870 ‘was not healthy for the Bengali mind and culture’ and that an ‘inferiority complex’ gripped the Bengali psyche – by Bengali, he meant Bengali Hindus – after exposure to Western education, knowledge and culture.

In 1867, Debendranath Tagore, along with poet-playwright-editor Nabagopal Mitra and essayist Rajnarayan Basu, took the leadership in organizing the Hindu Mela, which was alternatively called ‘jatiyo mela’ (national fair). The fair was inaugurated with a patriotic song composed by Rabindranath’s elder brother Dwijendranath –a polymath –addressing Bharat, the mother. ‘Malina Mukhochandra, Maa Bharat Tomari’ (You look pale, mother India). Towards the end of the 1870s, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay penned the hymn ‘Bande Mataram’. The hymn became part of his landmark and controversial literary work Ananda Math, published in 1882. It was a landmark for its literary value and social influence, and controversial for its anti-Muslim sentiment. Also, in 1882, in an article titled ‘Bangalar itihas sanmandhe koekti kotha’ (a few words about the history of Bengal) that appeared in Bangadarshan, which Bankim Chandra himself edited, Bankim refused to accept the history of Islamic rulers as the history of Bengal.

In our consideration, not a single English book contains the true history of Bengal. These books contain merely a hotchpotch of the birth, death and family feud of the Muslims who used to relax lying down on their beds wearing useless titles such as the Badshah of Bangalah or Subah-dar of Bangalah. This is not the history of Bengal; this is not even an iota of the history of Bengal. This has no connection whatsoever with Bengal’s history. The Bengali who accepts all this as the history of Bengal is not a Bengali. The one who accepts without questioning the versions of the Muslims, who are blind with self-pride are liars and Hindu-haters, is not a Bengali.

He also called upon Bengalis, in the same article, to search for and chronicle Bengal’s authentic history. By Bengalis, he meant Bengali-speaking Hindus.

Chadra Nath Basu’s book Hindutva was published in 1892 by Gurudas Chatterjee. The first recorded use of the word Hindutva, at least in print, is believed to have been made in this book. In the Calcutta Review’s July 1894 issue (Vol. 99), the ‘vernacular literature’ section carried a two-and-a-half- page review of Hindutva. The review describes the book as ‘evidently a work of Hindu revival’.

Though Hindu revivalism started as a counter narrative to Western education and culture, it gradually developed into Hindu nationalism seeking to confront the ruling British power. The primary sentiment was that Hindus are not inferior; they will not remain dominated.

In The Swadeshi Movement in Bengal (1903-1908), historian Sumit Sarkar wrote:

For a short while during its Derozian phase, the movement [the Renaissance] seemed to be heading for a really radical break with Hindu sectarian traditions and the achievement of a truly secular culture…. But as the century progressed, the awakening national pride of the Bengali bhadrolok sought sustenance more and more in images of ancient Hindu glory and medieval Hindu resistance to Muslim rule…. Patriotism tended to be identified with Hindu revivalism, ‘Hindu’ and ‘national’ came to be used as synonymous terms.

Ananda Math had emerged as an exemplar of the idea of Hindu nationalism. And in its aim of ousting the British, it did not consider taking the Muslims along. The first edition of the book merely excluded the Muslims in the Hindus’ fight against the British. In the second edition, though, the enemy changed from gora (white), British and sena (army) to ‘Nere’ and ‘Jobon’ – two derogatory terms by which the Hindus referred to the Muslims in Bengal.

According to Ahmed Sofa, a legendary public intellectual in Bangladesh, none influenced Bengal’s society and politics as much as Bankim did, and the influence of Ananda Math in Bengal’s socio-political life is comparable only to that of Jean Jacques Rousseau’s Social Contract in France. In Shotoborsher Ferari Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, while acknowledging Bankim’s literary genius, Sofa stressed that it was his thoughts on nation building that earned Bankim a distinct place. He was ‘more than merely a powerful writer,’ Sofa wrote, ‘He was the first to dream of establishing a Hindu Rashtra’, and added, ‘If a single person is to be blamed for the Partition of Bengal, it is Bankim Chandra.’

Hindu revivalism took a different shape at the beginning of the twentieth century, with the numerical increase of the Muslims, and the Muslim elites’ efforts to secure rights and benefits for the community.

Through June 1909, a string of letters, titled ‘Hindu: A Dying Race’, written by Lt Col. U.N. Mukerji, an Indian Medical Service officer, appeared in Bengalee, a Kolkata-based English-language newspaper owned and edited by veteran Congress leader Surendranath Banerjea. Historians identified these letters, later compiled into a pamphlet and also published as a book, as the founding basis of the notion that Hindus were in danger and they needed to wake up and act.

‘There are various ways people have dwindled and finally disappeared from their own country,’ Mukerji wrote, ‘and we are in a fair way of sharing their fate.’ He then explained how the Maoris of New Zealand and the natives of the US and Hispaniola disappeared following foreign invasions: ‘We are also a decaying race. Every census reveals the same fact. We are getting proportionately fewer and fewer….Year after year they [the Hindus] are being pushed back, the land once occupied by them is being taken up by Mohammedans, and their relative proportion to the population of the country is getting smaller and smaller.’

This excerpt from Mission Bengal: A Saffron Experiment by Snigdhendu Bhattacharya has been published with HarperCollins India.

A portrait of Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay | Wikimedia Commons

Nineteenth-century Bengal, the time and theatre of the Indian Renaissance from where many aspects of modern India originated, was also the birthplace of the idea of Hindutva, which the RSS describes as Hindu cultural nationalism. The very word Hindutva, the concept of Bharat Mata and the Bande Mataram slogan were all products of Bengal that spread across the country. The origin of the notion that Hindus are in danger – the principal reason that led to the creation of right-wing Hindutva organizations – can also be traced back to Bengal.

Hindu revivalism emerged in Bengal in the second half of the nineteenth century as a reaction to the influence of Western education and culture on the Hindu society during the first half of that century.

Brahmoism was a monotheistic socio-religious reformist movement born out of the Hindu society’s exposure to Western education. This movement sowed the seeds of the Bengal (or Indian) Renaissance. The movement denounced idolatry, faith in scriptures and avatars, and discrimination based on caste, creed and religion; it questioned superstitions and advocated women’s education. Its journey started with the foundation of the Brahmo Sabha in 1828 by ‘Rajah’ Rammohun Roy, the social, religious and educational reformer often regarded as the ‘father of Indian Renaissance’ and the ‘father of modern India’, and Debendranath Tagore, father of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore.

The visualization and depiction of India as a ‘mother’ started gaining popularity during the late 1860s. The first published reference to the coinage ‘Bharat Mata’ has been traced to a satirical Bengali book, Unabingsho Puran (the nineteenth purana), published in 1866 under the pseudonym of Krishnadwaipayana Vedavyasa. Bhudeb Mukhopadhyay, a scholar and writer, is generally regarded as its anonymous author. He was part of Bengal’s Hindu revivalism. Discussing Mukhopadhyay and his times, linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterjee wrote that the atmosphere in the colleges and high schools during 1840–1870 ‘was not healthy for the Bengali mind and culture’ and that an ‘inferiority complex’ gripped the Bengali psyche – by Bengali, he meant Bengali Hindus – after exposure to Western education, knowledge and culture.

In 1867, Debendranath Tagore, along with poet-playwright-editor Nabagopal Mitra and essayist Rajnarayan Basu, took the leadership in organizing the Hindu Mela, which was alternatively called ‘jatiyo mela’ (national fair). The fair was inaugurated with a patriotic song composed by Rabindranath’s elder brother Dwijendranath –a polymath –addressing Bharat, the mother. ‘Malina Mukhochandra, Maa Bharat Tomari’ (You look pale, mother India). Towards the end of the 1870s, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay penned the hymn ‘Bande Mataram’. The hymn became part of his landmark and controversial literary work Ananda Math, published in 1882. It was a landmark for its literary value and social influence, and controversial for its anti-Muslim sentiment. Also, in 1882, in an article titled ‘Bangalar itihas sanmandhe koekti kotha’ (a few words about the history of Bengal) that appeared in Bangadarshan, which Bankim Chandra himself edited, Bankim refused to accept the history of Islamic rulers as the history of Bengal.

In our consideration, not a single English book contains the true history of Bengal. These books contain merely a hotchpotch of the birth, death and family feud of the Muslims who used to relax lying down on their beds wearing useless titles such as the Badshah of Bangalah or Subah-dar of Bangalah. This is not the history of Bengal; this is not even an iota of the history of Bengal. This has no connection whatsoever with Bengal’s history. The Bengali who accepts all this as the history of Bengal is not a Bengali. The one who accepts without questioning the versions of the Muslims, who are blind with self-pride are liars and Hindu-haters, is not a Bengali.

He also called upon Bengalis, in the same article, to search for and chronicle Bengal’s authentic history. By Bengalis, he meant Bengali-speaking Hindus.

Chadra Nath Basu’s book Hindutva was published in 1892 by Gurudas Chatterjee. The first recorded use of the word Hindutva, at least in print, is believed to have been made in this book. In the Calcutta Review’s July 1894 issue (Vol. 99), the ‘vernacular literature’ section carried a two-and-a-half- page review of Hindutva. The review describes the book as ‘evidently a work of Hindu revival’.

Though Hindu revivalism started as a counter narrative to Western education and culture, it gradually developed into Hindu nationalism seeking to confront the ruling British power. The primary sentiment was that Hindus are not inferior; they will not remain dominated.

In The Swadeshi Movement in Bengal (1903-1908), historian Sumit Sarkar wrote:

For a short while during its Derozian phase, the movement [the Renaissance] seemed to be heading for a really radical break with Hindu sectarian traditions and the achievement of a truly secular culture…. But as the century progressed, the awakening national pride of the Bengali bhadrolok sought sustenance more and more in images of ancient Hindu glory and medieval Hindu resistance to Muslim rule…. Patriotism tended to be identified with Hindu revivalism, ‘Hindu’ and ‘national’ came to be used as synonymous terms.

Ananda Math had emerged as an exemplar of the idea of Hindu nationalism. And in its aim of ousting the British, it did not consider taking the Muslims along. The first edition of the book merely excluded the Muslims in the Hindus’ fight against the British. In the second edition, though, the enemy changed from gora (white), British and sena (army) to ‘Nere’ and ‘Jobon’ – two derogatory terms by which the Hindus referred to the Muslims in Bengal.

According to Ahmed Sofa, a legendary public intellectual in Bangladesh, none influenced Bengal’s society and politics as much as Bankim did, and the influence of Ananda Math in Bengal’s socio-political life is comparable only to that of Jean Jacques Rousseau’s Social Contract in France. In Shotoborsher Ferari Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, while acknowledging Bankim’s literary genius, Sofa stressed that it was his thoughts on nation building that earned Bankim a distinct place. He was ‘more than merely a powerful writer,’ Sofa wrote, ‘He was the first to dream of establishing a Hindu Rashtra’, and added, ‘If a single person is to be blamed for the Partition of Bengal, it is Bankim Chandra.’

By the end of the century, secret revolutionary societies started taking shape in Maharashtra and Bengal. Members of these groups were mostly bhadrolok – wealthy, upper-caste and educated Hindu Bengalis – but there were members from the lower castes too.

Muslims were not part of these groups. It appeared from the accounts of Bhupendranath Dutta and Hem Chandra Kanungo that Muslims were not welcome either. An integral part of their programme was taking oath on the Gita, while ‘Bande Mataram’ was their war cry. The members included some of Bengal’s most revered revolutionaries – from Bagha Jatin and Khudiram Bose to Master-da Surya Sen – who literally terrorized the British administration.

Hindu revivalism took a different shape at the beginning of the twentieth century, with the numerical increase of the Muslims, and the Muslim elites’ efforts to secure rights and benefits for the community.

Through June 1909, a string of letters, titled ‘Hindu: A Dying Race’, written by Lt Col. U.N. Mukerji, an Indian Medical Service officer, appeared in Bengalee, a Kolkata-based English-language newspaper owned and edited by veteran Congress leader Surendranath Banerjea. Historians identified these letters, later compiled into a pamphlet and also published as a book, as the founding basis of the notion that Hindus were in danger and they needed to wake up and act.

‘There are various ways people have dwindled and finally disappeared from their own country,’ Mukerji wrote, ‘and we are in a fair way of sharing their fate.’ He then explained how the Maoris of New Zealand and the natives of the US and Hispaniola disappeared following foreign invasions: ‘We are also a decaying race. Every census reveals the same fact. We are getting proportionately fewer and fewer….Year after year they [the Hindus] are being pushed back, the land once occupied by them is being taken up by Mohammedans, and their relative proportion to the population of the country is getting smaller and smaller.’

This excerpt from Mission Bengal: A Saffron Experiment by Snigdhendu Bhattacharya has been published with HarperCollins India.

Published/Broadcast by: The Print

Date published: 30 September, 2020 1:00 pm IST

Author: SNIGDHENDU BHATTACHARYA

Entry Type: Opinion